Chapter 4.

Biblical Archeology

Contemporary biblical archaeologists are in agreement that the “bible as history” is not compatible with their discoveries. In this chapter, I discuss the archeological evidence regarding the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, the source of the Christian Old Testament. The sections are as follows:

Note: BCE stands for Before the Common Era, that is, before the birth of Jesus of Nazareth.

Finding Meaning in the Bible

Many biblical stories are legend-like, abounding with miraculous and fantastic elements that strain the credulity of most modern readers, regardless of their religious persuasion. Biblical scholars have long known that the books of the Hebrew Bible were written long after the events that they purported to describe. Scholars have also recognized that the Bible as a whole is a composite produced by many writers whose contributions stretched over a thousand years. Furthermore, the biases of the ancient orthodox nationalists who contributed to the Bible are often painfully obvious, even to pious observers. These factors have all contributed to the rise of serious doubts about the Bible’s trustworthiness.

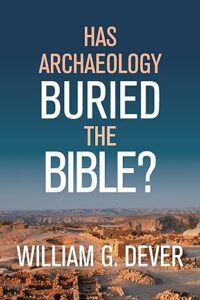

Based on archeological findings, a literal interpretation of biblical Scripture doesn’t hold up. However, there is another approach to comprehending scripture—as allegory. In Has Archaeology Buried the Bible?, William Dever describes allegory as “a literary or pictorial device in which characters stand for abstract ideas, principles, or forces, so that the literal sense has or suggests a deeper symbolic sense.” The original biblical writers and editors were basically story tellers, whose stories survived because they contained timeless and universal moral values. These stories are generally considered myths, not out of ridicule, but because they are deeply true in the sense of metaphor and allegory. This is reflected in the inspirational images created by many European artists.

Given the allegorical nature of Scripture, archaeology has the potential to shed light on the historical issue of what really happened. Archaeological data is unbiased, in contrast to biblical texts, which have been edited and reinterpreted for over two thousand years.

History of Near Eastern Archeology

About one hundred fifty years ago, American and British archaeologists began to work in the Near East. In the early to mid-20th century, most of the work was done by American theologists funded by Christian churches with the intention of confirming the Bible. However, beginning in the late 1960s, the work shifted its focus to the actual archaeological findings in the region, regardless of whether they confirm or refute biblical text. Soon, this secular branch of Near Eastern (Sino Palestinian) archaeology displaced the biblical archaeology movement, which had disintegrated due to the lack of evidence supporting the Bible stories.

Increasingly, with new discoveries that have been made since late in the 20th century, archaeology serves as an impartial observer to help scholars find new, authentic meanings in the biblical scriptures. William G. Dever, Ph.D., a prolific author and leading authority on biblical archaeology, has stated:

We archaeologists have indeed provoked a crisis for believers by introducing hard facts that challenge the simplistic readings of the Bible. The Bible is historical, but it reads more like a historical novel. It is authentic in that the places and the plot are realistic, the players are like real life characters from a certain time, but the book is fiction – believable fiction. If we archaeologists have forced new readings, we also point the way ahead, because in digging up a more realistic ancient Israel, we are not burying the Bible. We are bringing it to life again – not only for believers, but for any readers who believe that they can and must learn from the past.

Note: William G. Dever, Ph.D., is a professor emeritus of Near Eastern archaeology and anthropology at the University of Arizona. My research indicates that Dr. Dever is currently the world’s most prominent expert in biblical archaeology. I have used two of his books as resources: Has Archaeology Buried the Bible? and Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From?.

Scope of Coverage: Exodus and Conquest

To limit the scope of my discussion of Biblical Archaeology, I am focusing on the stories of probably the most well known epic in the Hebrew Bible—the Exodus from Egypt and the conquest of Canaan. This epic is thought to have originated in the 13th century BCE, which was a major developmental period of Israelite history. In those days, the Hebrews were nomads who were loosely organized into a confederation of twelve tribes that migrated over long distances with their flocks. In around the 13th century BCE, the tribes migrated into Canaan—their land of promise. The stories of this epic began as oral traditions told and then retold among the twelve tribes. Eventually the oral traditions were spelled out in written form, principally in the books of Exodus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, and Judges. However, writing did not become widespread until the 9th or 8th centuries BCE, so these books could not have been written until hundreds of years after the events that they claim to describe. In fact, modern scholars estimate that the biblical texts about the Exodus and conquest of Canaan were initially produced much later, in the 6th century BCE, with final revisions in the 5th century BCE.

To investigate the historical accuracy of these stories, I will focus exclusively on the events that qualify for archaeological scrutiny: archeological sites associated with the Hebrew Bible. This area of study is primarily in the Near Eastern region of Palestine and primarily covers the Iron Age (1200–500 BCE). The biblical archaeologist William Dever, quoted above, wrote in 2020, “The crucial pieces of the puzzle have come together only in the last twenty-five years, so many of the handbooks are obsolete.”

Exodus from Egypt: History or Myth?

According to the Hebrew Bible, in about the 13th century BCE, Moses and “about 600,000 (Israelite) men on foot” with their families left Egypt (Exodus 12:37-42), crossing the Red Sea. They then walked into and across the Sinai desert, wandering for almost 40 years. Finding evidence of Moses leading a mass of Israelite slaves out of Egypt is problematic. There is nothing about this event written in the numerous collections of Egyptian texts.

The story about crossing the Red Sea is controversial. The Hebrew term “yam suf” does not mean “Red Sea”. The word suf was mistranslated in the Latin and Greek renditions. A more literal meaning of this Hebrew term is “Reed Sea”. Yet, even though there are references to the Reed Sea and its location (Exodus 14:2), such a shallow crossing of the waters has never been found.

The crossing of the Sinai Desert is also problematic. If one calculates the addition of woman and children to the 600,000 men, the total could be estimated as high as 3,000,000 Israelites. According to Dever, “The problem is that anyone who has ever traversed the Sinai and camped there (as I have) knows that the vast arid wastes of the desert could not have possibly supported even a small, straggling band of a few hundred – certainly not for thirty-eight years… The biblical story, read literally, is simply not credible.”

The wilderness itinerary (Exodus 20-40; Numbers 1-33) mentions dozens of sites where Moses and his followers traveled and camped in both the Sinai desert and Transjordan (the Southern Levant east of the Jordan River). Archaeologists have made a concerted effort to identify and locate these sites in the Sinai desert. However, according to Dever, only two can be located with any confidence.

Another prominent story in the Hebrew Bible is that of Moses and the Ten Commandments. The story relates that Moses went up to Mount Sinai and received two stone tablets called “the tablets of the covenant.” These tablets contained the Ten Commandments, said to have been written by Yahweh, the Hebrew monotheistic deity. These commandments codified basic biblical principles relating to ethics and worship that remain fundamental to Judaism. However, according to Dever, there is no data of any kind to support the existence of Mount Sinai, despite many attempts to identify it.

The Conquest of Canaan

The last phase of the Exodus epic is the conquest of Canaan (Canaan, or Phoenicia, occupied much of the Eastern Mediterranean—the Levant). The conquest is described in the books of Joshua and Numbers.

Under Moses’s leadership, the twelve Israelite tribes defeated king after king and destroyed numerous settlements. Moses died at the age of 120 and was replaced by Joshua. A competent military leader, Joshua began by leading his troops in the destruction of Jericho, which is famous for mighty walls that “came tumbling down.” The Israelites continued fighting, eventually conquering all the cities in Canaan—destroying “all who breathed” (Joshua 10:40). They triumphed again and again because “Yahweh, the God of Israel, fought for Israel” (Joshua 10:42).

The Israelites then moved northward, seizing the city of Hazor, “the head of all of those kingdoms” (Joshua 11:10). They burned the city to the ground and killed the king. Thereafter, the other cities in the north were all conquered. According to the books of Joshua and Numbers, the Israelites ended up destroying more than thirty Canaanite cities and kings. Once the land was completely pacified, Joshua divided it among the twelve confederated tribes of Israel. The journey to establish the Holy Land was finally completed.

Archeological Sites in the Land of Canaan

Of the more than thirty sites that the books of Joshua and Numbers claim were “utterly destroyed”, only a handful have been identified and excavated. The information in this section is drawn from Has Archaeology Buried the Bible?, William G. Dever.

Note: For a summary of the estimated dates of the archeological sites, see Timeframe Summary, below.

These sites include: Heshbon, Dibon, Jericho, ‘Ai, and Hazor:

- Heshbon: A prominent mound, Heshbon was extensively excavated by a team of excellent Seventh Day Adventist archaeologists from 1968 to 1978. They were undoubtedly hoping to find destruction levels dating to the late 13th century BCE or so. However, what they discovered was only a small unprotected village, hardly the land of Sihon, which was said to be vast. Moreover, the site was unoccupied before the 12th to 11th centuries BCE (between 1200–1001 BCE). These archaeologists admitted Heshbon to be “the first casualty of the war,” meaning their own battle to confirm Scripture.

- Dibon: In the 1950s and 1960s, Southern Baptist scholars excavated the site of Dibon, only to find that no remains existed before the 9th century BCE (between 900-801 BCE). This was a “city” that was destroyed before it was even there!

- Jericho: This site, which is the largest mound in the lower Jordan valley, was excavated several times in the 20th century. According to Dever, this site was destroyed by the Egyptians circa 1500 BCE. Thereafter, it was virtually deserted until the founding of a small Israelite town in the 7th century BCE (between 700–601 BCE). As with Heshbon and Dibon, there was no Canaanite city to demolish; no walls to come tumbling down.

- ‘Ai: The next site to have been identified is ‘Ai, the destruction of which is described in Joshua 6-7. The location of this great twenty-seven-acre mound is undisputed. ‘Ai has been excavated twice: in 1933-1935, by French archeologists, and in 1964-1970, by a team directed by Southern Baptist scholar Joseph Callaway. Callaway’s team found no supporting biblical evidence at ‘Ai. By about 2500 BCE, the site was entirely abandoned; not a single Late Bronze Age potsherd was found on the entire site. It remained deserted long after the conquest of Canaan, until in probably the 12th century BCE (1200–1101 BCE) a small Israelite village was founded on top of the ancient ruins. There is no evidence of Israelite destruction.

- Hazor: Out of the over thirty cities said to be destroyed, perhaps Hazor is the only candidate that could qualify as having been destroyed by the Israelites. Hazor, “the head of all those kingdoms” (Joshua 11), was extensively excavated by leading Israeli archaeologists in 1955-1958 and 1990-2017. It is generally believed that Hazor was destroyed by the Israelites. However, there is a conflicting hypothesis that the destruction occurred during an internecine war between rival Canaanite rulers, so the matter remains unsettled.

William Dever sums up the lack of archeological corroboration: “…Joshua is almost certainly a work of fiction, celebrating in an exaggerated fashion the exploits of a legendary military hero.”

Timeframe | Archeological Age | Biblical Timeline | Archeological Timeline |

500s BCE | Iron Age

| Finalized Exodus & Conquest texts |

|

600s BCE | Initial texts about Exodus & Conquest |

| |

700s BCE |

| Small Israelite resettlement at Jericho | |

800s BCE | Writing became widespread |

| |

900s BCE | Dibon first occupied | ||

1000s BCE |

|

| |

1100s BCE |

|

| |

1200s BCE |

| Small Israelite resettlement at ‘Ai; Heshbon first occupied (sometime after 1200 BCE) | |

1300s BCE | Bronze Age | Estimated time of Exodus and Conquest | Hazor destroyed (by Israelites or rival Canaanites) |

1400s BCE |

|

| |

1500s BCE |

| Jericho destroyed by Egyptians | |

. . . |

|

| |

2500 BCE |

| Original ‘Ai abandoned |

My view all along—and especially in the recent books—is first that the biblical narratives are indeed ‘stories,’ often fictional and almost always propagandistic, but that here and there they contain some valid historical information. (Has Archaeology Buried the Bible?)

Tel Aviv University archaeologist Ze’ev Herzog wrote in the Haaretz newspaper:

This is what archaeologists have learned from their excavations in the Land of Israel: the Israelites were never in Egypt, did not wander in the desert, did not conquer the land in a military campaign and did not pass it on to the 12 tribes of Israel. Perhaps even harder to swallow is that the united monarchy of David and Solomon, which is described by the Bible as a regional power, was at most a small tribal kingdom. And it will come as an unpleasant shock to many that the God of Israel, YHWH, had a female consort and that the early Israelite religion adopted monotheism only in the waning period of the monarchy and not at Mount Sinai.

Israel Finkelstein, an Israeli archaeologist, a professor emeritus at Tel Aviv University and co-author of The Bible Unearthed has also weighed in. He told The Jerusalem Post that Jewish archaeologists have found no historical or archaeological evidence to back the biblical narrative on the Exodus, the Jews’ roaming in Sinai, or Joshua’s conquest of Canaan. Finkelstein also said that there is no archaeological evidence to prove that the Temple of Solomon actually existed, and independent archaeologist Professor Yoni Mizrahi concurred with Finkelstein. Of course, the lack of evidence for the grand Temple of Solomon as described in the book of Kings does not prove the absence of a temple of some sort.

Regarding the Exodus of Israelites from Egypt, Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass, as quoted in The New York Times, said, “Really, it’s a myth, …This is my career as an archaeologist. I should tell them the truth. If the people are upset, that is not my problem.” (The New York Times, April 3, 2007; “In Sinai desert, no trace of Moses,” by Michael Slackman.)