Chapter 3.

Hebrew Bible

The literature of faith in Judaism is the Hebrew Bible. This is a collection of Hebrew Scriptures that coalesced over time into twenty-four books. The Hebrew Bible is neither a scientific examination nor a historical description. It is the story of religious beliefs and a repository of cultural and human values.

Geographically, the land of the Hebrew Bible consists of mountains and hills, valleys and plains, fertile land and desert. Some biblical names are still recognizable today, among these: Sea of Galilee, Jordan River, Red Sea, and, of course, Jerusalem. The Hebrew people had a Bedouin or pastoral nomadic lifestyle. They were not farmers, but herders with flocks of goats and sheep. They lived, not in houses, but in tents.

Transporting their goods on camels or donkeys, they traveled long distances in search of pastureland and water for their flocks and beasts of burden. Though aware of cities and towns along the way, they generally avoided them. Their nomadic groups were large, consisting of closely related multigenerational families.

John Shelby Spong (who was an American bishop of the Episcopal Church, a biblical scholar, and the author of two dozen books) has summarized the historical context of the Hebrew Bible as follows:

The historic saga of Israel that begins in slavery in Egypt and wanders through the wilderness to the conquest of Canaan, to the establishment of a united kingdom that endured division and civil war, defeat and exile, only to return to their holy land, is a narrative written by a variety of persons over half a millennium. It is filled with geographical misinformation and biological, geological, and astrophysical information only of this ancient time. It reflects cultural traditions long since abandoned as unworthy of civilized people—polygamy, child sacrifice, and slavery, for example.

In this chapter, I discuss the origins of the Hebrew Bible and then appeal to Christian fundamentalists to reconsider their relationship to the Old Testament, which is essentially identical to the Hebrew Bible. This chapter contains the following sections:

Note: BCE stands for Before the Common Era, and CE stands for Common Era. The biblical scripture is from the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV).

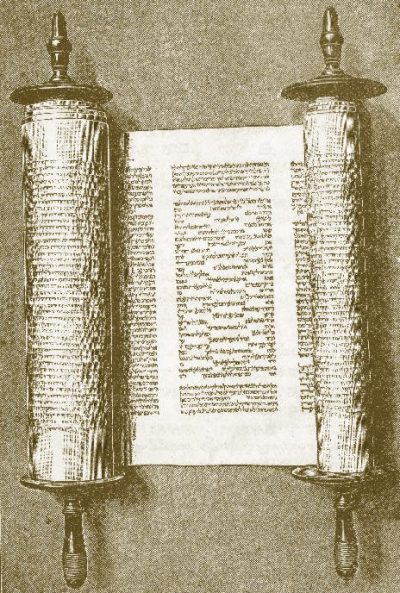

The Torah

In my consideration of issues in the Hebrew Bible, I limit my coverage to the Torah. “Torah” is the Hebrew name for the first five books of the Hebrew Bible (the Torah is also called the Pentateuch or the Five Books of Moses). The five books of the Torah are: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.

Anachronisms in the Torah

Biblical chronology is very complicated and inexact, so anachronisms are highly likely in the Torah. According to biblical tradition, Abraham, the Patriarch, was thought to have been born in the 20th century BCE and to have died in the 19th century BCE. But the oldest source of biblical writing dates from the 10th century BCE. This means that about nine hundred years elapsed between Abraham’s lifetime and the recording of his life. For nine centuries, Abraham’s story must have been told around campfires, passing orally from generation to generation. How much historical truth could have survived in a nine-hundred-year-old oral tradition?

The same chronological problem exists for Moses, who was the Israelites’ leader and lawgiver and the most important prophet in Judaism. Traditionally, Moses is regarded as the author of the Torah, but Biblical archeology has shown that Moses died some 300 years before the earliest words of the Torah were written: The Torah’s traditional date for the Exodus of Moses and the Israelites from Egypt is 1446 BCE yet all current scholars and even evangelicals agree that, based on archaeological evidence, the only timeframe that the Israelites could have emerged in Canaan is significantly later, circa 1230-1170 BCE.

Mosaic Authorship?

“Mosaic authorship” refers to the traditional belief that the Torah was dictated to Moses by God. Mosaic authorship was contested by some early biblical scholars, for whom the idea that Moses alone wrote the entire Torah became problematical. Contradictions in the text caused them to doubt Mosaic authorship. I will mention just a few of the many contradictions.

The five books of the Torah included things that Moses was not likely to have said nor could even have known. In the 11th century (CE), Isaac ibn Yashush, a Jew who was a court physician for a ruler in Muslim Spain, pointed out that a list of Edomite kings in Genesis 36 named kings that lived long after Moses was dead. In the 12th century, one rabbi pointed to biblical passages that referred to Moses in the third person. These passages used language from a time and a locale other than those of Moses and used terms that Moses could not have known. Much later, in the 15th century, Tostatus, Bishop of Avila, noted that the account of Moses’s death could not have been written by Moses.

In the 17th century, Thomas Hobbes, the British philosopher, came right out and said that Moses did not write the majority of the Torah. Hobbes presented numerous cases throughout the five books that were inconsistent with Mosaic authorship. About the same time, the Dutch philosopher Spinoza published a unified critical analysis showing many contradicting and problematic passages. Among these is Deuteronomy 34:10, “Never since has there arisen a prophet in Israel like Moses, whom the Lord knew face to face.” Spinoza pointed out that this sounded like the words of someone who lived long after Moses and was able to make a comparison to later prophets.

One of the statements frequently used to bolster the perspective that Moses could not have written these five books appears in Numbers 12:3, which reads: “Now the man Moses was very humble, more so than anyone else on the face of the earth.” After reading this statement, the question arises: How could Moses be the meekest or most humble man on the face of the earth and then proceed to tell everyone that he is?

Today, formal support for Mosaic authorship is limited largely to conservative Evangelical Christians. Richard Elliott Friedman, a premiere U.S. Bible Scholar and bestselling author of eight books on the Bible, states, “At present, there is hardly a biblical scholar in the world actively working on the problem who would claim that the Five Books of Moses were written by Moses — or by any one person.” (Who Wrote the Bible?, R.E. Friedman, 2019)

But if Moses was not the author of the Torah, then who was?

Origins of Hebrew Scripture: The Documentary Hypothesis

Through the ages, Christians and Jews have accepted the Bible as literal sacred scripture. However, in the 18th century, several European biblical scholars independently uncovered and documented irregularities in the Torah. They noted two kinds of evidence: “doublets” (the same story being told twice) and the use of different names of God in different versions of a story.

These scholars found a frequent occurrence of doublets in the Torah. Some examples are two versions of the creation of the world; two stories of the covenant between God and Abraham; two accounts of the naming of Abraham’s son, Isaac; and two stories of a revelation to Jacob at Beth-el. The scholars also noticed that often one version of a doublet would refer to God as Yahweh (the name for God in Judah) and the other version, as Elohim (the name for God in Israel).

A German biblical scholar, Julius Wellhausen, published an influential volume in 1878 (second edition in 1883) that correlated the history and development of the Torah to the development of Judaism. Wellhausen presented an emergent hypothesis about the origins of the Torah that became known as the documentary hypothesis. The documentary hypothesis gives insight into how and when the stories of the Bible arose.

Wellhausen hypothesized that four separate sources contributed to the Torah. Today, the exact number and origin of Torah sources remains a gray area. For example, two recent variations include the supplementary hypothesis and the fragmentary hypothesis. Still, among modern biblical scholars, the widely held view is that some variation of the documentary hypothesis explains how the Torah came to be written.

I am limiting this discussion to the basic four sources. These were written independently and, one by one, were merged into one more-or-less continuous narrative. These sources are called Yawist (J or Y), Elohist (E), Deuteronomic (D), and Priestly (P). Typically, biblical scholars refer to these sources simply by their initials. To refer to merged sources, their respective initials are concatenated; for example, JED represents Yawist-Elohist-Deuteronomic.

The authors of these sources are unknown, but it is clear that each source reflects the agenda of its author(s). Multiple authors are believed to have contributed to the Deuteronomic and Priestly sources. The authorship of the Yawist and Elohist sources is less apparent, so a single author is typically ascribed to each.

Note: Biblical scholars have long assumed that the authors were men because women were seldom taught to read and write in that era.

Historical Context

After the death of King Solomon, a rebellion in about 920 BCE against the royal house of David and the temple led to a civil war in the Hebrew nation. As a consequence, the land was divided into a northern kingdom, called Israel, and a southern kingdom, called Judah. It is hypothesized that the Yawist document was written in the southern kingdom (Judah) and the Elohist document was written in the northern kingdom (Israel). In 722 BCE, the northern kingdom was conquered by Assyria, causing some people to flee southward to Judah. About a century later, around 622 BCE, the Deuteronomic (D) source appeared in Judah and subsequently was added to the JE source (resulting in the JED text).

Then, in about 587 BCE, Judah was conquered by Babylon. Over time, many of Judah’s people were forcibly exiled to Babylonia, where the Priestly text was written and blended into the JED text. The exile ended in 538 BCE, and some of the exiled Judeans returned to Judah.

The following table summarizes the chronology of the biblical sources and their blending.

|

Source |

Date |

Region |

|

Hebrew kingdom split |

ca. 920 BCE |

|

|

Yawist (J/Y) |

922–722 BCE |

Southern Kingdom (Judah) |

|

Elohist (E) |

922–722 BCE |

Northern Kingdom (Israel) |

|

Conquest of Samaria by Assyria |

722 BCE |

Northern Kingdom escapees flee to Judah. |

|

Merging of J and E (JE) |

8th century (after 722 BCE) |

Judah |

|

Deuteronomic (D) discovered |

ca 622 BCE |

|

|

Addition of D to JE (JED) |

622–596 BCE |

|

|

Exile to Babylonia |

597–581 BCE |

Babylon |

|

Priestly (P) revision (JEDP) |

ca. 597–538 BCE |

|

|

Exiles return |

539 BCE |

Judah |

|

Redactor (integration of J, E, D, & P into full Hebrew Bible) |

5th century BCE |

The Yawist Source (J)

An unknown author in the kingdom of Judah, most likely between 922–722 BCE, wrote a series of epic stories about how the Judaic nation came into being. The author called God by the name of Yahweh, so the narrative is called the Yahwist document. The Yawist stories have been influenced by other sources, but under the scrutiny of biblical scholars, the Yawist source document clearly stands on its own.

The document opens with the creation story, continues with the sagas of Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph, and ends with the account of Moses. The Yawist author’s creation story shows a human-like God with a concern for humanity. The beginning of a primitive monotheism is clearly evident, as the stories proclaim that Yahweh is the only divine power in the universe.

The author’s reason for telling these stories appears to have been to establish a history of his people and the role of Yahweh in their society. The Jerusalem temple and the royal house of David were the commanding institutions in Judah, and the author viewed authority as vested in the monarchy and the temple. He saw the line of authority as originating from God, then flowing to the king and the priests as His anointed ones, and only then, to the people.

The Elohist Source (E)

In Israel (the northern kingdom), the rebellion against the Jerusalem temple and the royal house of David had to be rationalized, and a new form of government had to be created. Without the temple or a sustaining royal family, a new interpretation of history was needed. This interpretation was recorded in a document composed sometime during the life of ancient Israel, the northern kingdom (922–722 BCE). The document, which called God by the name Elohim, is known as the Elohist document.

The Elohist author created a story that incorporated a value system that stood against the royal dynasty and the temple. His narrative suggested that God’s original covenant was made, not with Moses or the royal family, but with the people, who then choose their own leaders. As a result, no king, leader, or priest could claim everlasting power over God’s people. The Israelite leaders were to be responsible to the people and could be removed if they did not uphold their duty. This was the blossoming of a democracy.

It is clear that the Elohist author was a citizen of Israel. His narrative presents distinct versions of many stories that were also in the Yahwist document. The Elohist narrative began not with the creation, but with Abraham, whose grandson Jacob became the focus of the narrative. Jacob came to life as a heroic figure, who encountered many amazing adventures. The Elohist document was an attempt by the author to explain the origins of Israelite society by reshaping the history of a past that occurred possibly a thousand years or more earlier. He may have known some of the details of the Yahwist document, but he downplayed the emphasis on Judah to highlight the glory of Israel.

In 722 BCE, the capital of Israel, Samaria, fell to the Assyrians and many of the people of Israel were forced into exile. However, others escaped Assyrian captivity. They rescued the Elohist document, taking it to Jerusalem in Judah. There, in the 8th century BCE, the Elohist narrative was blended into the Yahwist narrative. The blended document (JD) was the second phase in the formation of the Torah. However, the effort to integrate these two narratives was never completed. Many of the contradictions in the Torah are the result of the incomplete blending of these two originally separate and distinct versions of the historical narrative.

The Deuteronomist Source (D)

Another major modification of this sacred story occurred in Jerusalem around 622 BCE. A scroll of law that was claimed to have been written by Moses was “discovered” in the temple. The scroll called for religious reforms that the priests wanted and revitalized a kind of national pride. The text was called the second (deutero) bestowing of the law (nomas), and came to be called Deuteronomy.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, “D uses a distinctive vocabulary and style of exhortation to call for Israel’s conformity with Yahweh’s Covenant laws and to stress Yahweh’s election of Israel as his special people.” (Deuteronomist | biblical criticism | Britannica)

King Josiah read and embraced the text and called his people into a renewed covenant and reform movement. In the following twenty-five years, this text was added to the Yahwist-Elohist (JE) document as the book of Deuteronomy. It is clear that more than one person was involved in creating the JED version. Those early Deuteronomic writers conceived of Yahweh as monolatrous. Their agenda was to purify the land and centralize worship under the Jerusalem priesthood, to purge all foreign rites from Judah, and to help the people realize the love that Yahweh had for them. The authors instructed that no image of God could be used in worship. They continued the tradition of Yahweh as a nationalistic deity. All religious shrines were closed down except for the Jerusalem temple, and they decreed that Passover could only be celebrated in Jerusalem. This new document gave their people a sense of national history and identity.

Twenty-five years after the book of Deuteronomy was discovered, the Babylonians destroyed Judah. Many of the Judeans went into captivity in Babylon, but they brought the blended version of the Yahwist-Elohist-Deuteronomist sacred story and traditions with them.

The Priestly Source (P)

The deportation into Babylonian exile of the ruling class and many others began about 596 BCE, and the exile (or captivity) lasted until 538 BCE. In the ancient world, captivity usually meant the end of a nation’s life. Historically, a conquered people would over time be assimilated into the new culture by intermarriage and eventually lose its identity. This is what had happened to the exiled Israelites of the northern kingdom when they were resettled by Assyria 130 years earlier.

In Babylon, everything that the displaced Judeans stood for was in jeopardy. However, they were resilient individuals. Led by their priestly class, they met this national identity crisis by maintaining and strengthening the governance of Judaic religious traditions over the life of the people.

Judeans maintained their national identity in captivity by appearing and behaving differently from their captors. The priestly group led in the construction of synagogues to provide exclusively Judean gathering places. To reinforce the distinct Judean identity, the priests resumed two traditions that had fallen into disuse: circumcision and observance of the Sabbath. The circumcision of every male created a physical sign on their bodies that set them apart from the general population. The last day of the Babylonian week, Saturday, became the Judean Sabbath, and none of the Judeans worked on Saturday. At some point, partly as a result of the Babylonian captivity, a common Jewish identity began to emerge for the people of Judah, regardless of tribe.

During the almost six decades of Babylonian captivity, members of the priestly class created a revision of the Torah that codified and supported Jewish identity. The Yahweh deity of Judah prevailed over the Elohim deity of Israel. The priestly authors thoroughly edited the Yawist-Elohist-Deuteronomic (JED) portion of the Hebrew sacred story. They revised Deuteronomy to describe Yahweh in monotheistic terms and added substantial new material.

The new material made the Priestly source the largest source of the Torah, about the size of the other three sources put together. The rules and observance of worship became essential and resulted in the addition of parts of the book of Genesis, much of the book of Exodus, almost the entire book of Leviticus, major segments of the book of Numbers, and an addition to the end of Deuteronomy. The resulting document is known as the Priestly source.

The new creation story was one of the last parts of the Hebrew Scriptures to be completed. The familiar seven-day creation story that opens the Bible was written to connect the Sabbath day observance to the moment of creation (Genesis 2:3): “So God blessed the seventh day and hallowed it, because on it God rested from all the work he had done in creation.”

In addition, the Ten Commandments were updated to mandate the keeping of the Sabbath. According to John Shelby Spong:

The Ten Commandments of Exodus 20 were edited to place the rationale from the new creation story into the words of Moses requiring the Jews to keep holy the Sabbath day. All the chronologies in the Old Testament are from the hand of the priestly writers. They wanted to make sure that the links with the past were kept intact. A history of every ritual observed in Jewish worship entered the sacred story.

The Priestly source incorporated ancient priestly traditions, as well as new traditions introduced as new commandments for faithful Jews. According to Spong:

The story of Abraham was altered to place the origin of the practice of circumcision into the life of the founding father of Israel. Strict dietary laws were written into the Torah as part of the separatist movement. Kosher food is a gift to Jewry of the Priestly writer in exile in the late sixth and early 5th century BCE.

Jewish tradition states that there are 613 commandments in the five books of the Torah. This number was established in the 3rd century CE by Rabbi Simlai and confirmed by Maimonides in the 12th century CE. The multi-faceted efforts of the priests maintained the separate identity for the exiled Judeans and, eventually, for Judaism as a whole.

Redactor

In addition to the four sources outlined above, there was very likely a final important contributor, an editor, who rearranged texts that already existed, without writing much new text. He would have been someone with credibility who possessed the editorial skills to combine and reorganize originally separate documents, thereby merging them into a coherent single work that would be readable as a continuous narrative. This editor is known as the “redactor.”

In the entire bible only two men are known as lawgivers—Moses and Ezra, who resided in Babylon during the captivity. Richard Elliott Friedman, biblical scholar and author of the recent book, Who Wrote the Bible?, has made a convincing case that the redactor who assembled the four sources into the Five Books of Moses (the Pentateuch) was Ezra. Ezra was a scribe and an Aaronid priest, who had the backing of the Babylonian emperor. Friedman notes that some other investigators have agreed that Ezra may have been the individual who constructed the Five Books of Moses.

Note: The following video presents an illustrated introduction to the documentary hypothesis: The Origins Of The Torah – The Documentary Hypothesis (13:14).

An Appeal to Christian Fundamentalists

The Hebrew Bible is as central to Christianity as it is to Judaism. Early Christians incorporated and slightly adapted the Hebrew Bible into the Christian Bible as its “Old Testament.” The Old Testament consists of essentially the same material as the Hebrew Bible, but in thirty-nine books instead of twenty-four. The Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament are generally regarded as authoritative scriptures for their respective religious communities. In the Christian Bible, the Old Testament provides a foundation for the New Testament. Without the Hebrew Bible, Christianity would not be what it is today. Nevertheless, most Christian scholars today accept that the Hebrew Bible is not the literal word of God, but a document written across many centuries by men who reflected their particular social and cultural contexts and evolving religious practices.

However, even today, most Evangelical Christians pay little or no attention to the question of authorship and still believe that some or much of the Torah can be traced to Moses. The following two quotations from John Shelby Spong’s book Rescuing the Bible from Fundamentalism are directed to Christians who claim that the bible is literally the inerrant “Word of God:”

- Spong:

Do we really want to worship a God who plays favorites, who chooses one people to be God’s people (Israelites) to the neglect of all the others? When we portray the God of the Bible as hating everyone that the chosen people hate, is God well served? Will our modern consciousness allow us to view with favor a God who could manipulate the weather in order to send the great flood that drowned all human lives save for Noah’s family because human life had become so evil God needed to destroy it? … Can we really worship the God found in the Bible who sent the angel of death across the land of Egypt to murder the firstborn male in every Egyptian household in order to facilitate the release of the chosen people? Can the Bible still be of God when it portrays Joshua as stopping the sun in the sky for the sole purpose of allowing him the time to slaughter more of his enemies, the Amorites (Joshua 10:12-15)? Can the Bible be the ‘Word of God’ when it has Samuel order King Saul in the name of God to ‘Go and Smite Amalek, and utterly destroy all that they have; do not spare them, but kill both man and woman, infant and suckling, ox and sheep, camel and ass’(1Samuel 15:3)? … These are but a few of the questions I want the Bible quoters to answer. Is Christianity somehow irrevocably linked to this mentality because of our continuing claims for the Bible?

- Spong:

I am now convinced that institutional Christianity has become so consumed by its quest for power and authority, most of which is rooted in the excessive claims for the Bible, that the authentic voice of God can no longer be heard within it.

Regardless of denomination, how many Christians, if any, sitting in church on Sunday learn about the bible based on modern biblical scholarship?