Chapter 10.

History of Heaven and Hell

There was a time in Western Civilization when the ideas of heaven and hell did not exist. But of the over two billion Christians alive today, most believe in some version of heaven or hell. According to a recent Pew Research poll, 72% of all Americans believe in a literal heaven and 58% believe in a literal hell. How did this happen? Who invented heaven and hell, and how did these ideas evolve over time?

In this chapter, I discuss the origins of the modern notions of heaven and hell. The sections are as follows:

Note: BCE stands for Before the Common Era, that is, before the birth of Jesus of Nazareth, and CE stands for Common Era, which began with the birth of Jesus. The biblical scripture is from the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV).

Ancient Views of the Afterlife

Fear of death has led to humanity’s profound preoccupation with whether there is life after death. For an early perspective on this subject, I look back to ancient Mesopotamia, Greece, and Rome. In this section I survey beliefs of ancient poets and philosophers about what happens after death.

The Epic of Gilgamesh (ca. 2100–1200 BCE)

In the mid-19th century, an epic poem about an ancient Mesopotamian hero, Gilgamesh, was discovered in Assyria (located in what is now northern Iraq and southeastern Turkey). The Epic of Gilgamesh is one of the oldest and longest literary compositions known in the native language of ancient Mesopotamia. Gilgamesh is a mythical superhero whose journey consists of many encounters with death. He tells his friend what it is like in the afterlife, “If I tell you… you must sit (and) weep! …” (Epic of Gilgamesh, Tablet XII, iv). This reflects the terror of death that has haunted western peoples for at least as long as we have written records.

The Iliad and the Odyssey (ca. Late 8th Century BCE)

Around the late 8th century BCE, the Greek poet Homer wrote two epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey. Among the oldest existing literary works in Western culture, these two epics have had great significance for the culture and religion of ancient Greece and in the centuries that followed.

Homer’s epic poems portray the departed as joyless ghosts with no possibility of passion or pleasure of any kind. Those who have not been properly buried are displaced to a no-man’s land between the living and the dead. Only those who have been properly buried are completely dead. According to Achilles, a protagonist in the Iliad, the realm of the dead is a place “where the senseless, burnt-out wraiths of mortals make their home” (Odyssey, Book 11, line 540).

In the Odyssey, three of the characters died after committing serious crimes against the gods. Rather than just being displaced to a bland no-man’s land, their ghosts were condemned to Hades. There, they would suffer eternal torment for their crimes. The torment of these three souls would later serve as a model of hell in the Christian tradition.

Pythagoras (570-495 BCE)

Pythagoras is well known for one of his main teachings, metempsychosis, or “the transmigration of souls.” Transmigration holds that all souls are immortal, and, upon death, the soul enters into a new body, that is, they reincarnate. Pythagoras appears to have been unusual in believing in reincarnation in ancient Greece, though reincarnation is a long-standing spiritual tradition in China, India, Japan, Tibet, and other parts of the East.

Socrates (470-399 BCE)

A Greek philosopher from Athens, Socrates is considered one of the founders of western philosophy. He was the first moral philosopher of the western ethical tradition. In 399 BCE, Socrates was put on trial both for “not believing in the gods of the state” and for corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens. He was found guilty and died of state-mandated hemlock poisoning.

That same year, Plato, a student of Socrates, wrote about Socrates defending himself before a jury in Athens. Plato gives Socrates’s view of what happens at death: “Death is one of two things. Either it is annihilation, and the dead have no consciousness of anything, or, as we are told, it is really a change – a migration of the soul from this place to another” (Plato’s Apology 40c). Thus, according to Plato, Socrates believed that if his soul were not annihilated, it would reincarnate.

Plato (Around 425-347 BCE)

Plato is considered a key figure in the history of ancient Greek and western philosophy, and his work has had a major influence on Christianity.

Plato used both traditional myths and myths he invented as a forum for presenting his ideas. He developed the idea of postmortem justice for both the wicked and the virtuous. He viewed the immortal soul as the real person, and the body as gross material that is to be left behind. When the soul leaves the body, it goes off to a favorable or miserable fate. The underlying message of his myths: a life of virtue will bring its own reward; wickedness leads only to misery.

Plato seems to have believed in reincarnation. The following advice is widely attributed to him, “Apply yourself both now and in the next life. Without effort, you cannot be prosperous. Though the land be good, you cannot have an abundant crop without cultivation.”

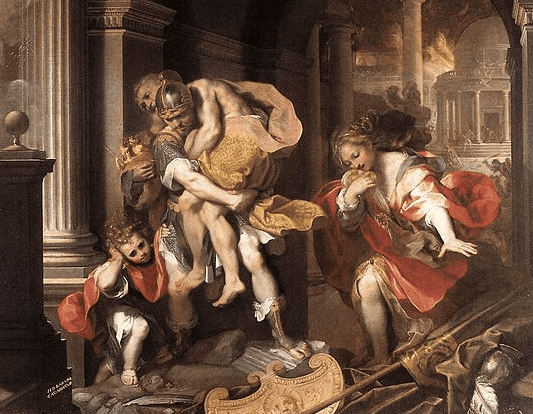

Virgil (70-21 BCE)

Centuries after the Greek philosophers, the poet Virgil appeared in Rome. Virgil is traditionally considered one of Rome’s greatest poets. He is famous for his twelve-book epic poem, Aeneid, featuring the hero Aeneas. The Aeneid is considered to be the history of the origins of the Roman people and is one of the most important early works in Western literature. Though similarities exist between the afterlife journeys in Virgil’s Aeneid and those of Odysseus in Homer’s Odyssey, there are important differences. In the Odyssey, the souls of the deceased all experience the same boring and pleasure-free existence. In contrast, like Plato, Virgil believed that those who sinned would be punished: in the Aeneid, departed souls experience either suffering or pleasure, depending on their behavior while living in a body.

Virgil also believed in reincarnation. All souls would eventually be able to reincarnate, though those who sinned would be punished before they were able to move on.

What precipitated Virgil’s ephemeral version of heaven and hell? A shift in ethical thinking had occurred between the times of Homer and Virgil. Thinkers came to believe that good behavior should be rewarded and evil punished. No one could harm others while alive and get away with it in the afterlife.

Old Testament (Hebrew Bible)

The conceptions of death found in the Hebrew Bible likely informed Jesus and his Jewish followers. Their Jewish perspectives are entrenched in the largest portion of the Christian Bible, the Old Testament, which is a slightly modified version of the Hebrew Bible.

The conception of death in the Hebrew Bible is very complex with varying interpretations among scholars. Here, I quote pertinent parts of a summation by Dr. T. Desmond Alexander, Senior Lecturer in Biblical Studies at Union Theological College in Ireland. Dr. Alexander has authored fifteen books, mostly centered on the Old Testament. In the conclusion of his extensive article, The Old Testament view of life after death, he states:

While some of the evidence is ambiguous, and questions remain to be answered, we are perhaps now in a position to clarify certain fundamental issues regarding the Old Testament perception of the after-life. …it seems probable that the [Hebrew] term Sheol frequently, if not always, designated the nether world, and that as such it represented the continuing abode of the ungodly. …whereas the wicked were thought to remain in the dark, silent region of Sheol, the righteous lived in the hope that God would deliver them from the power of death and take them to himself. (cf. Ps. 49:15)

Another biblical scholar, New York Times bestselling author Bart D. Ehrman, Ph.D., M.DIV., states in Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife:

There is unanimity among biblical scholars that in no case does Sheol mean “hell” in the sense people mean today. There is no place of eternal punishment in any passage of the entire Old Testament. In fact—and this comes as a surprise to many people—nowhere in the entire Hebrew Bible is there any discussion at all of heaven and hell as places of rewards and punishment for those who have died. (Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife)

Jewish beliefs in the afterlife shifted over time. At the birth of Christianity, most Jews believed in some version of the doctrine of an apocalyptic Day of Judgment followed by resurrection of the righteous. This doctrine was contrary to the pagan view that at death, the soul leaves the body. According to Ehrman:

[The doctrine of resurrection was a belief] in a future restoration and resuscitation of the body that did not involve simply a temporary return to life but an entrance into life eternal, not lived as a disembodied soul but as a unified person, body and soul…. They believed it was the body that would be raised on the Day of Judgment, when the righteous would be given eternal life and the wicked would be annihilated for all time. (Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife)

New Testament

As Christianity developed, the conception of life after death evolved, but it did not reflect the beliefs of Jesus of Nazareth nor those expressed in the Hebrew Bible.

Apostle Paul: on Baptism and Salvation

Other than Jesus, Apostle Paul (Born 5 BCE to 5 CE; Died 67 CE) was the most important figure in early Christianity. Paul spread the nascent Christian religion among the pagans, and as a result, two and a half centuries after his death, Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire.

Paul taught that the initiation rite of baptism was utterly fundamental. Unlike the pagans, Paul did not believe in the soul and, therefore, did not believe in the immortality of the soul. Paul incorporated a form of Jewish apocalyptic thought but taught that only those who were baptized and believed in Jesus’ death and resurrection could expect future salvation. For Paul, “resurrection” always meant resurrection of the body. He believed that bodily resurrection was possible for his followers, and he imagined that their resurrected bodies would be completely transformed: These bodies will be “flesh and blood” bodies that are perfect and immortal.

Paul’s concept of the resurrection was very complicated, and details won’t be covered here, except to say that, at the return of Jesus, the followers of Christ would inherit eternal salvation. On the other hand, unbelievers would experience “sudden destruction” (1 Thessalonians 5:3), being annihilated—taken out of existence, but without torment or suffering.

The early followers of Jesus expected God’s glorious kingdom to come right away. Until the last years of his ministry, Paul believed that in his own lifetime, Jesus was going to return for the resurrection. Paul had no way of knowing that hundreds of years later the Roman Catholic Church would have invented and adopted the doctrine that after death, all souls would spend an eternity in heaven or hell.

For more information on Paul, see the Kingpins of Christianity and Discover Jesus without Dogma chapters.

Origins of Christian Heaven and Hell

Given that Paul had no conception of heaven or hell, how did the Christian concepts of heaven and hell come into being?

When God’s glorious kingdom failed to come right away, Christian writers became inclined to modify what Paul had taught. By the time the earliest gospels were written, 40 to 60 years after the death of Jesus, Paul’s vision of the imminent salvation and resurrection of believers was uncertain.

By that time, thanks largely to Paul’s ministry, most Christian communities were comprised of former pagans. These Christians had been raised with the Greek view of the immortality of the soul and of reward or punishment after death. This is reflected by the fact that all four synoptic gospels were written in Greek, not in Aramaic, the language of the first apostles. In line with their pagan perspectives, the writers of the later gospels, Luke and John, moved away from the teaching of the kingdom of God on Earth to the teaching of God’s kingdom in heaven. This kingdom in heaven is available after death to all who believe and are baptized, that is, to the righteous. However, eternal life entails rewards and punishments. Thus, the Christian teaching of heaven above and hell below emerged.

Much of the teaching about heaven and hell comes from the unknown author of the two-volume works of Luke and Acts. This author is thought to have been a Greek-educated Christian who wrote around 80–85 CE. Unlike in the apocalyptic theory of Paul, the righteous reap rewards immediately upon death, without waiting for the resurrection.

The most recent gospel in the New Testament is John, which was written about 60 years after Jesus’ death. Here, some remnants of the apocalyptic view survive, but the author of John wrote mostly about heaven above and how people can get there by believing in Jesus (and being baptized). Also, compared to earlier gospels, John contains more references about rewards and punishment in the present moment—in this life.

By the 2nd century CE, relatively few Christians believed in an imminent apocalypse. Instead, their views were consistent with today’s beliefs of heaven and hell. By the 3rd century, the standard view had become the teaching of postmortem rewards and punishment, to be eventually followed by a resurrection. This is still the belief of many of today’s Christians.

Descriptions of Heaven and Hell

A few representative descriptions of heaven and hell in the New Testament follow:

- Revelation 21:18-21

The Book of Revelation inspired the metaphor of the entryway into heaven as “pearly gates:”

The wall is built of jasper, while the city is pure gold, clear as glass. The foundations of the wall of the city are adorned with every jewel; the first was jasper, the second sapphire, the third agate, the fourth emerald, the fifth onyx, the sixth carnelian, the seventh chrysolite, the eight beryl, the ninth topaz, the tenth chrysoprase, the eleventh jacinth, the twelfth amethyst. And the twelve gates are twelve pearls, each of the gates is a single pearl, and the street of the city is pure gold, transparent as glass.

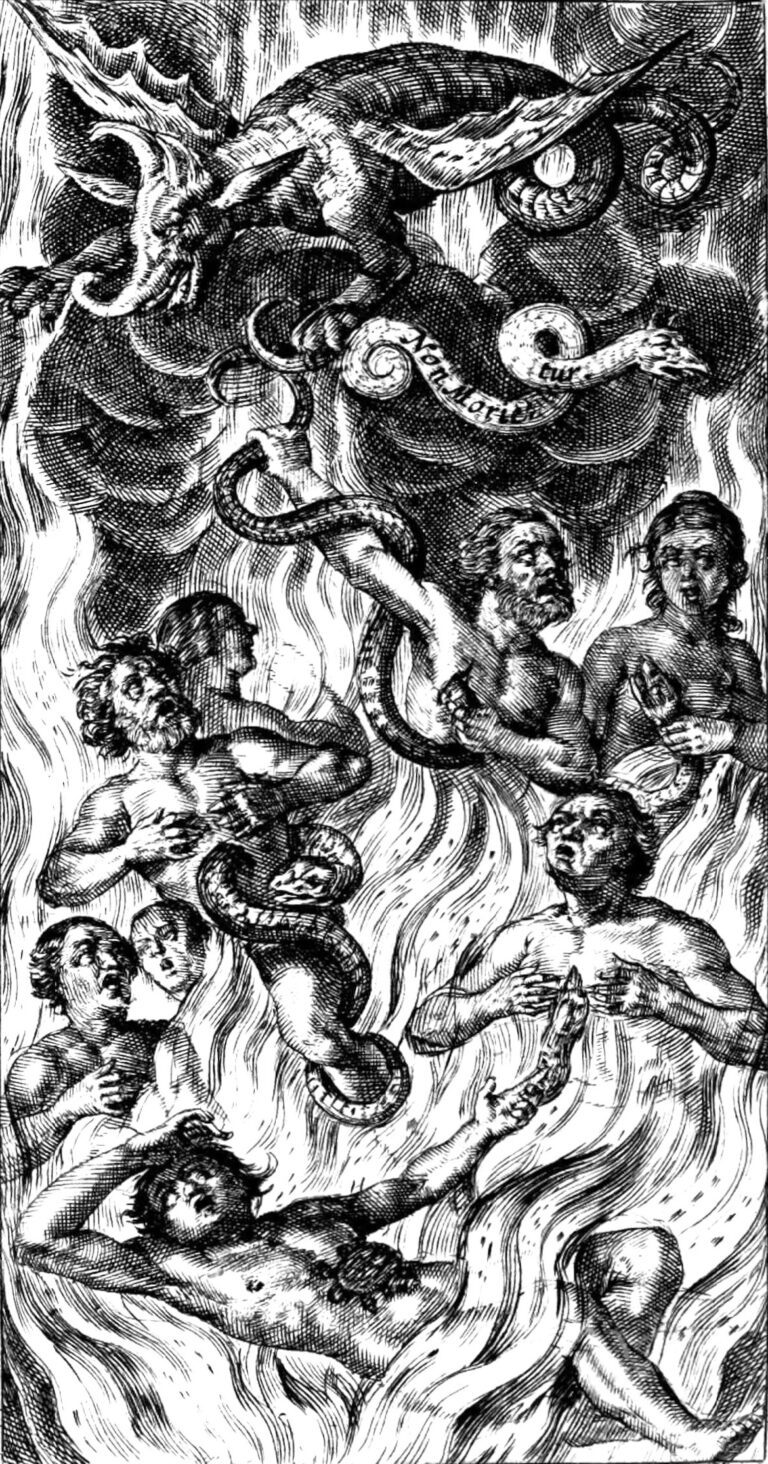

- Revelation 21:8

The Book of Revelation expresses an early view of the fires of hell:

But as for the cowardly, the faithless, the polluted, the murderers, the fornicators, the sorcerers, the idolaters, and all liars, their place will be in the lake that burns with fire and sulfur, which is the second death.

- Matthew 13:41,42

The Book of Matthew also describes an early view of the fires of hell:

The Son of Man will send his angels, and they will collect out of his kingdom all causes of sin and all evildoers, and they will throw them into the furnace of fire, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.

Post New Testament

Tertullian (155–220 CE), who has been called the “founder of Western theology,” was hugely influential on later theologians. Tertullian may have been the first to allude to “mortal sins.” He was a prolific author whose seminal work, Apology, was completed in 197 CE. Here’s Tertullian’s take on heaven and hell: “After the present age is ended he [God] will judge his worshipers for a reward of eternal life and the godless for a fire equally perpetual and unending” (Tertullian’s Apology 18:3). The wicked would not be annihilated as Paul had predicted but would be subject to eternal torment.

In 367 CE, over a century and a half after Tertullian produced his Apology, the final form of the New Testament was established as authoritative. It was made official by the Council of Rome in 382 CE, when Christianity was becoming the dominant religion of the Roman Empire.

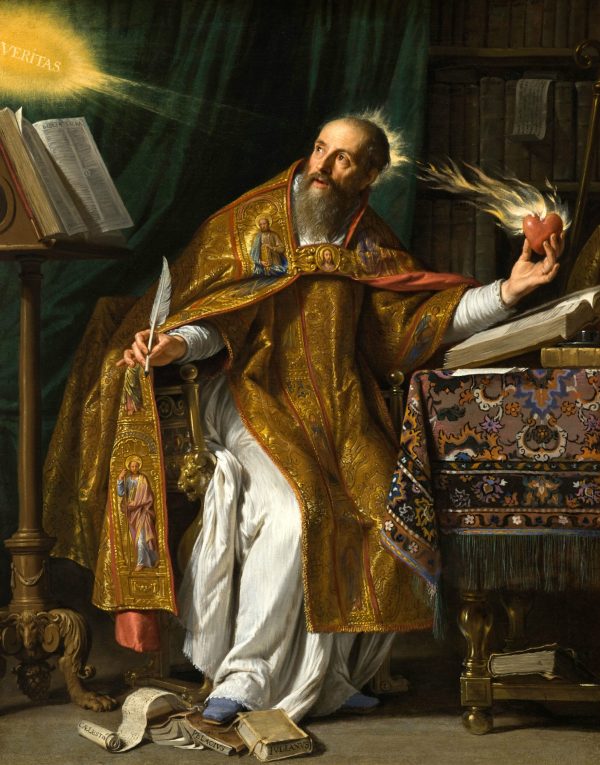

Though the eventual resurrection of the body remained the main doctrinal view, many objections were raised. These were addressed by Augustine, Bishop of Hippo. Augustine (354–430 CE) was the most influential theologian of Christian antiquity (for more information, see the Kingpins of Christianity chapter). Perhaps taking a cue from Tertullian, Augustine believed that eternal torment for the damned and eternal ecstasy for the saved would come only with God’s final judgment at the end of the world.

Augustine left unresolved issues. One was a question regarding the people who were destined to be saved but had committed venial (non-mortal) sins. Wouldn’t they have to endure torments to purge them of their sins? Centuries later the resolution of this question was to become known as the doctrine of purgatory. In Roman Catholic doctrine, purgatory is a place or state of punishment wherein Catholic souls who die in God’s grace may make satisfaction for past sins and so become fit for heaven (Merriam-Webster Dictionary) . The Catholic Church institutionalized purgatory as official doctrine in 1274 and it remains in effect to this day.

Note that, generally, Protestants do not believe in purgatory. One reason they have rejected this doctrine is because it is not supported by biblical scripture.

In Conclusion

Beliefs about the afterlife in Western thought have evolved substantially over several millennia. Ancient poets in Mesopotamia, Greece and Rome contrived various stories about the afterlife. Eventually, in ancient Greece, philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras promulgated his afterlife belief of reincarnation, and Socrates believed that if his soul was not annihilated at death, it would reincarnate.

By the beginning of Christianity, many Jews believed that on the Day of Judgment the righteous will be bodily resurrected by God and taken into His Presence and that the wicked will be annihilated. The first Christians retained the Jewish belief in an apocalypse followed by resurrection or annihilation, but as we know, that has never happened. Eventually, hundreds of years after the death of Jesus, the Roman Catholic Church established its doctrine of either eternal salvation in heaven or eternal punishment in hell, neither of which has any basis in reality.

Typically, Christian denominations teach their followers what to do to get into heaven and to stay out of hell. However, they offer their congregations very few details about the purported heaven and hell. In fact, for most of Christianity’s existence, valid information about the afterlife was unavailable in Christian communities. During this time, Christians generally accepted whatever they were told on this subject.

Today in the Information Age

In the years that researchers have been studying the afterlife, there is no evidence whatsoever to support the Christian idea of an eternity in heaven or hell. Today, more and more Christians are seeing through that false dogma. Many modern Christians are turning to more substantial perspectives on the afterlife. According to 2021 data released by the Pew Research Center, 30% of Christians in the U.S. believe in reincarnation, which is 9% more than in their 2009 survey.

Now, in the information age, there are likely thousands of books written about the afterlife by people without any religious agenda. An exploration of afterlife research can offer a fascinating look at reality beyond the physical plane of existence. I have carefully investigated and selected over 200 books on the afterlife for the Science-Based Awakening Library. Reference-links to these books are distributed among the following resource pages: Near-Death Experiences, Out-of-Body Experiences, Reincarnation, Mediumship, and Death and Dying.