Chapter 13.

Christianity: Religion of Fear and Hope

According to the Center for the Study of Global Christianity, it is estimated that there are more than 200 Christian denominations in the U.S. and about 45,000 globally. The diversity of doctrine among these churches is unfathomable. However, the vast majority of them have historical roots in the church that became the official religion of the Roman Empire in 380—known today as the Roman Catholic Church.

The Roman Catholic Church has been the most important religious movement in the history of western civilization. It held a virtual monopoly on Christian doctrine in Europe until the Protestant reformation in 1517. For this reason, this chapter focuses on Roman Catholicism, which is still the world’s largest Christian religion with over 1.2 billion Catholics alive today. In the remainder of this chapter, I generally refer to the Roman Catholic Church simply as the Church.

Note: CE stands for Common Era, which began with the birth of Jesus. The biblical scripture is from the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV).

This chapter outlines the evolution of western Christianity after the death of Jesus. I discuss the role of false dogma, sacraments, exploitation, schisms in Christianity, and the business model of Christian churches. The sections are as follows:

The Beginning: The Church Claims Authority

The Church considers one of the original twelve apostles, St. Peter, to be its foundation. This belief rests upon a biblical passage in the Gospel of Matthew, which was written 40 to 50 years after the death of Jesus (ca. 33) (for more information, see the New Testament chapter):

And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven. [italics added for emphasis] (Matthew 16:18-19)

Note: In Greek mythology, Hades is the god of the dead, whose name became synonymous with the underworld. Notice that this passage does not use the word “hell.”

This biblical passage attributed to Jesus appears to justify the authority of the Roman Catholic Church. This passage became the doctrine for declaring that Peter was the first pope and for establishing papal succession in the Church. However, there is no historical or biblical evidence for this claim—even Catholic historians accept this as a historical fact. Furthermore, German scholar and author Otto Zwierlein wrote in his Petrus Und Paulus in Jerusalem Und ROM, “There is not a single piece of reliable literary evidence (and no archaeological evidence either) that Peter ever was in Rome.”

To further establish itself as the institution responsible for administering to Jesus’ followers, the Church has used a second biblical passage (John, 21:16-17), wherein Jesus says to Peter, “Tend my sheep…Feed my sheep.” Based on this passage, the pope eventually became known as the Vicar of Christ—the “earthly representative of Christ.” The first pope to be called the Vicar of Christ was St. Gelasius I, who was pope from 492 to 496 (Saint Gelasius I | Biography, Papacy, & Facts | Britannica).

The validity of the tend-my-sheep passage is dubious. Modern biblical scholars agree that the source of the Gospel of John, the youngest of the four canonical gospels, was not the Apostle John. The vast majority of Johannine scholars view John as a book that underwent a chain of revisions by distinct authors over a period of fifteen or more years. Scholars generally place its original version in the 90s with final revisions completed by 110 (for more information, see the New Testament chapter).

As I have shown, the Church’s claims to be Christ’s representative on Earth and to have been charged with looking after his flock are based only on New Testament passages written two or more generations after Jesus’ death. How could these writers know forty to eighty years after Jesus died that he spoke these words? Nothing was recorded when he spoke, and it is virtually impossible that any of these writers were ever with him in person.

Despite the lack of any valid spiritual authority, by the 4th century, the Catholic Church was a formidable enough institution to begin accruing political authority. In the early part of the 4th century, the Church gained the backing of Emperor Constantine. After Constantine gave his blessing to the Church, it developed into a powerful institution. By the time it became the official religion of the Roman Empire in 380, its churches, bishops, priests, and deacons were already widespread throughout the Roman Empire. For more information, see Constantine the Great (272–337) in the “Kingpins of Christianity” chapter.

Sin

The doctrine of sin is central to Christianity. Sin is generally defined as an act or offense against God by despising his persons and Christian biblical law, and by injuring others. The Christian notion is that sin is endemic to humankind. Christians believe that humanity dwells in a state of sin as the result of the fall of man, which presumably occurred in the mythical Garden of Eden. This occurred because of the biblical Adam’s disobedience in consuming fruit from the tree of knowledge of good and evil.

According to the influential teachings of Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, Adam’s “original sin” created a tainted nature that all humans inherit simply by being born. Original sin is characterized in many ways by theologians, ranging from something like a slight deficiency or propensity to sin without any collective guilt (referred to as “sin nature”) to total depravity of all humans through collective guilt. Essentially, however, in all the interpretations of sin, humanity is characterized as innately flawed and in need of rescue. For more information, see the Original Sin chapter.

Church dogma soon codified two classes of sin: mortal sin and venial sin. Tertullian may have been the first to suggest, in the latter half of the 2nd century, a distinction between mortal and venial sins. Subsequently, the Church adopted this teaching on sin, and it became standard in the Church. The Church defines mortal sin as a gravely sinful act which can lead to damnation if the offender does not properly repent of the sin before death. For a sin to qualify as mortal, it must be a grave matter, the offender must have full knowledge that the sin is mortal and must have the offender’s deliberate consent. A venial sin is a lesser offence against God and is not subject to eternal damnation.

In 365, Pacian, bishop of Barcelona, listed murder, fornication, and contempt of God as prime examples of mortal sins. Later, in 393, St. Jerome wrote about both classes of sin, “There are venial sins and there are mortal sins… There is a great difference between one sin and another.” After committing a mortal sin, to avoid damnation after death, a person needed to repent by confessing to a clergyman and completing the penance that he prescribed (this process is known as Confession or Reconciliation). Only then was the mortal sinner of Jerome’s era eligible to receive communion again.

These two classes of sin remain Church doctrine to this day. But the originally small number of types of mortal sins of the early Church has seen remarkable growth. Currently, the Church identifies over one hundred mortal sins; for a list of these, see psalm91.com. Today, however, Catholics can cleanse their souls of mortal sin by making a “perfect act of contrition” without going to a priest. Venial sins have never required confession before communion, though all modern Catholics are bound by an obligation faithfully to confess serious sins at least once a year.

What made the Church believe that sin is real and that it had the right to invent classes of sins?

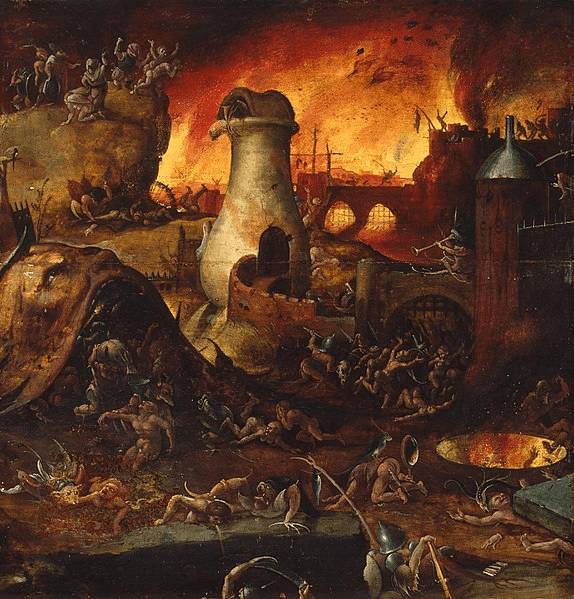

Creating Hell

The Christian concept of eternal punishment of any soul (which is an individuated, unique unit of pure consciousness and universal unconditional love) in hell is just that, a Christian concept. It has no basis in reality. This idea did not come from the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) which makes up approximately 75% of the Christian Bible. According to Bart Ehrman, biblical scholar and New York Times bestselling author of 30 books on the Bible, “The ideas of a glorious hereafter for some souls and torment for others, to come at the point of death, cannot be found either in the Old Testament or in the teachings of the historical Jesus. To put it succinctly: the [traditionally named] founder of Christianity did not believe that the soul of a person who died would go to heaven or hell.” Ehrman continues, “The ideas of heaven and hell were invented and have been altered over the years.” (Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife).

However, despite the lack of any historical or biblical precedent, “hell” has become a “biblical” staple. The Church has been using the word hell in its Bible for centuries. For example, in 1582, when the Catholic Church translated its Latin Vulgate Bible into the English Douay-Rheims Bible, to counter the Protestant Reformation, the translators used the word hell. For instance, Matthew 5:22 states, “… And whosoever shall say, Thou Fool, shall be in danger of hell fire.”

Note that, when uttered with contempt, spite, or malice, “Thou fool” was looked upon as a heinous injury, and therefore was severely condemned. According to commentary on the Douay-Rheims Bible Online, “…hell fire [was] literally, according to the Greek, …the Gehenna of fire.” In biblical times, “Gehenna” was a valley just outside Jerusalem that served as a burning garbage dump. The bodies of executed criminals or individuals denied a proper burial would be dumped there. In rabbinic literature Gehenna is also a destination of the wicked, but this is distinct from the Christian notion of “eternal hell fire.”

The use of hell in biblical translations persists. For example, in the New Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition of the Bible (1993), the word hell still appears in Matthew 5:22: “…and if you say, ‘You fool,’ you will be liable to the hell of fire.” In the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV), published in 1989 by the American National Council of Churches, this passage also says, “…you will be liable to the hell of fire”.

The Church has long made its definition of hell quite clear. In the most recent Catechism of the Catholic Church, Second Edition (1994, 1997, 2019):

The teaching of the Church affirms the existence of hell and its eternity. Immediately after death the souls of those who die in a state of mortal sin descend into hell, where they suffer the punishments of hell, ‘eternal fire’. The chief punishment of hell is eternal separation from God, in whom alone man can possess the life and happiness for which he was created and for which he longs. (Catechism of the Catholic Church,1035)

For more information, see the History of Heaven and Hell chapter.

Salvation

The concept of salvation springs from the early Christian idea of sin. In religion, salvation generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its after-death consequences. Fear of death is central to the human psyche: “There are several psychological theories that place fear of dying as our greatest fear and a huge motivating force” (Psychology Today, posted on the internet June 23rd, 2017). Salvation is a state of being saved or protected from harm after death. The hope of salvation potentially eases the fear of going to hell.

Among Christian denominations, there are various views on salvation. According to the Catholic Church, the death of Jesus is a sacrifice that redeems man and reconciles him to God—except for unrepentant mortal sinners, who are condemned to hell. Sinners can repent and be forgiven only through the Church’s sacraments of Baptism and Confession. Only a Catholic who dies without mortal sins is eligible for heaven—”the ultimate end and fulfillment of the deepest human longings, the state of supreme, definitive happiness.” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1024)

Church Dogma

The Church defines a dogma as, “a truth revealed by God, which the magisterium of the Church declared as binding.” The magisterium is the authority claimed by the Church to give authentic interpretation of the Word of God, “whether in its written form or in the form of Tradition.” The Church Catechism states:

The Church’s Magisterium asserts that it exercises the authority it holds from Christ to the fullest extent when it defines dogmas, that is, when it proposes, in a form obliging Catholics to an irrevocable adherence of faith, truths contained in divine Revelation or also when it proposes, in a definitive way, truths having a necessary connection with these. (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 88)

All dogmas are doctrines—teachings or beliefs taught by the magisterium of the Church, though not all doctrine is dogma.

A major development of Church dogma occurred in the 4th century, when Cyril, Bishop of Jerusalem, (313–386) finished a lengthy, nearly complete dogmatic treatise with instructions and initiations in Church doctrine. The Catholic Church adopted Cyril’s treatise as a manual of doctrinal operations for its bishops, priests, church members, and candidates for conversion to Catholicism. The modern English version of this treatise, Catechetical Lectures of St. Cyril of Jerusalem is a 753-page book.

Among Cyril’s many topics were doctrines on the following:

- Baptism: Some of the perceived “benefits” of Catholic baptism are the forgiveness of prior sins and the making of the baptized person into a member of the Church. Baptism is perceived to mark the soul of the person as belonging to Christ.

- Holy Eucharist (Communion) and transubstantiation: The perceived benefit for partaking of the Eucharist for a Catholic is that they receive the real presence of Jesus. Reception of His presence is said to be the result of transubstantiation, “…that (which) appears to be bread is not bread, though perceived by the taste, but the Body of Christ, and what appears to be wine is not wine, though the taste says so, but the Blood of Christ…”

- Confirmation: Some of the perceived benefits that the Church confers on those receiving confirmation are a completing of the baptismal covenant, the bestowal of full membership in the Church, and a strengthening between the recipient and the Church.

- Hell: “… but if a man is a sinner, he shall receive an eternal body, fitted to endure the penalties of sins, that he may burn eternally in fire, nor ever be consumed.” (Catechetical Lectures, 18:19 [A.D. 350]). In 1274, over nine hundred years after Cyril, the Church dogma incorporated the notion of purgatory, where Catholic souls who die in God’s grace but have sinned can become fit for heaven.

These elements of doctrine are still central in today’s Catholic faith.

Sacraments

In the early church, the clergy administered the rites for three sacraments: Baptism, Confirmation, and Communion (Holy Eucharist). These original three sacraments were expanded to seven at the Council of Trent (1545–1563). The sacraments that were added later are Marriage, Reconciliation (also known as Confession or Penance), Anointing of the Sick (formerly known as Extreme Unction), and Ordination (also called Holy Orders). None of the sacraments can be received unless administered by a Catholic clergyman, such as a priest or bishop. Today, in addition to participating in required sacraments, a Catholic must abide by the Catechism of the Catholic Church, which contains 904 pages of dogma and doctrine.

The sacraments and Catechism are powerful social control mechanisms. Social control is also evident in restrictions on the priesthood, which is limited to celibate men. To become a Catholic priest, a candidate must complete the requisite training, become a deacon (who is unmarried, celibate, and chaste), and finally receive Ordination into the priesthood from a bishop. The challenges of the vow of celibacy have been demonstrated by recent exposés of sexual abuses by Catholic priests.

Since early days, Church members have been encouraged to convert non-Christians to the catholic brand of Christianity. Non-Christians were (and still are) told that if they believe in Jesus and are baptized and comply with the Church’s teachings, they would be saved; otherwise, they would be condemned. Early Church leaders understood the use of fear and hope.

To become official members of the Church today, non-Christian initiates must be willing to go through the ritual of Baptism and learn Church dogma through the Confirmation process conducted by clergy. The initiates learn about mortal sins. If they have committed one of these and want to avoid damnation when they die, they need to repent by confessing to a clergyman and completing the Penance (Confession or Reconciliation) that he prescribes. After the confirmation process, the initiates receive the sacrament of Confirmation and become official Church members.

Next, I will look in more detail at Baptism and at Confession and Repentance.

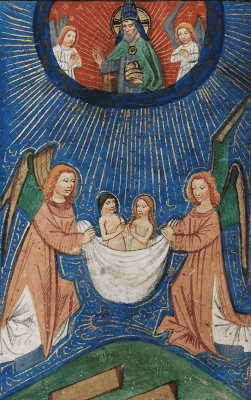

Baptism

The Church insists that baptism is required for salvation. It maintains that, as Christ’s purported representative on Earth, charged with looking after his flock, it has the sole authority to baptize people, as well as a duty to do so. The Church’s belief system surrounding baptism holds that everyone not baptized is tainted with original sin because they are descendants of Adam. Only Baptism can free people from the grip of original and personal sin.

The requirement of baptism depends on passages from books of the New Testament: the gospels of Mark and John and the Book of Acts, all of which proclaim the necessity of baptism for salvation.

These passages are presented here in the chronological order of these books:

- In the Gospel of Mark, after Jesus rose from the dead, he is quoted as having said to the eleven apostles who remained after Judas Iscariot’s betrayal, “And he said to them, ‘go into all the world and proclaim the ‘good news’ to the whole creation. The one who believes and is baptized will be saved; but the one who does not believe will be condemned. [italics added for emphasis]” (Mark 16:15-16).

Mark was written at least forty years after the death of Jesus. Its anonymous author is believed to have written in Rome for a Christian community. It is unlikely that this author ever heard Jesus speak. According to James Edwards in The Gospel According to Mark, there is recent acknowledgement of the author of Mark as a theologian and an artist who used a range of literary devices to express his concept of Jesus.

- In the Book of Acts, baptism is supported by a passage in which Peter is preaching to a crowd about how their own sins, together with the help of wicked men, crucified Jesus. The crowd responded, “What shall we do?” Peter said to them, “Repent, and be baptized every one of you in the name of Jesus Christ so that your sins may be forgiven; and you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit” (Acts 2:38). The same message is restated in Acts 22:16. The message here is that everyone is a sinner, and in order to have their sins forgiven by God, they must be baptized in the name of Jesus Christ.

Modern biblical scholars are in agreement that the Book of Acts was written by the anonymous, non-eyewitness who also wrote the Gospel of Luke. According to New York Times bestselling author John Shelby Spong, these two books are thought to be the work of an evangelist who wrote in Caesarea sometime between the years 83 and 90, over fifty years after the death of Jesus. It is very doubtful that the author of Luke and Acts ever heard Jesus speak.

- In the Gospel of John, the requirement of baptism for salvation is found in the following verse: “Jesus answered, ‘Very truly, I tell you, no one can enter the kingdom of God without being born of water and Spirit’” (John 3:5).

The writing of John, the last gospel, did not begin until about 60 years after the death of Jesus, extremely late for any of its authors to have heard Jesus speak.

Given that nothing was recorded when Jesus spoke, it is probable that these passages were all invented by the authors of these books. For more information, see the New Testament chapter.

In the original Nicene Creed (of 325), there was no mention of baptism, though it had long been a Christian practice. At some point in the 4th century, the Church dictated specific instructions to believers before they could be baptized. The baptismal ceremony was complex. A series of rites and instructions were spread over several weeks leading up to Easter, when the baptism would finally occur. The baptism rite involved a bishop consecrating the holy water and administering the baptism. People were baptized by submersion, immersion, or by water being poured on their head. People who went through this lengthy process became members of the Catholic Church, which represents itself as the “Body of Christ.” They believed that their sins were forgiven and that they were now capable of attaining salvation and avoiding damnation.

In 380, the Catholic Church became the official church of the Roman Empire. Only one year later, in 381, the Nicene Creed was revised to require baptism for salvation, substantiating it in the Church’s dogma: “we acknowledge one baptism for the remission of sins.”

Note: The institutionalization of the Church continued to move very quickly. Pope Damasus I presided over the Council of Rome in 382. To help legitimize Church authority, this council established a complete list of the canonical books (those declared by the Church to be of divine inspiration and officially accepted as genuine) of both the New Testament and Old Testament. Excluded gospels were labeled heretical. The Christian Bible was then official. These books still comprise the Christian Bible as we know it today.

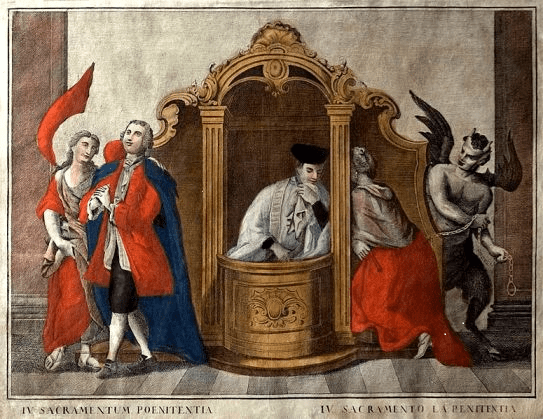

Confession and Repentance (Penance or Reconciliation)

In general terms, repentance is turning from sin and dedicating oneself to the amendment of one’s life. The belief of the early Church elaborated by Tertullian and other Church fathers was that repentance was sufficient to remove sins committed after baptism. Repentance, which later became known as the sacrament of penance/reconciliation, began with the sacrament of Confession. Penance consisted of certain exercises such as prayer and alms.

Before the 4th century, the confession of sin was public. Basil, Bishop of Caesarea (330–379) wrote about early penitents who committed a mortal sin such as murder, adultery or fornication and the requirements for their confession and repentance. Bishops did not grant remission of these penitents’ sins, but consulted with them and assigned them the proper penance. An example of public penance for an adulterer would be fifteen years of prescribed penance (Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: Second Series, Volume 8 – Basil: Letters and Select Works, Letter 217, Canons 56, 57, 58, p. 256; 1995). Upon completion of the prescribed penance, the adulterer’s sin would be forgiven, and he or she would be able to receive the sacraments, such as communion, and was no longer facing eternal damnation. However, this was a one-time reprieve; if the adulterer (or any such penitent) committed another mortal sin, it would not be forgiven.

In the 7th century the doctrine for penance was relaxed so that a bishop could prescribe penance every time a sinner committed a mortal sin. Apparently, repeat offenders had become a significant problem for the Church.

The process of the forgiveness of sins went through an additional series of complex changes over the centuries. These are far too complicated to cover here. Instead, I will look only at the current practice. Briefly, a penitent typically goes into a confessional booth in a Catholic church, where a priest is waiting to hear confessions. A privacy screen separates the penitent from the priest. The penitent confesses his or her sins and then does the penance that the priest assigns. To qualify for forgiveness, an essential part of the process is the penitent being sincerely sorry for the sins and truly resolving not to commit them again. Confession of venial sins lessens one’s time in purgatory.

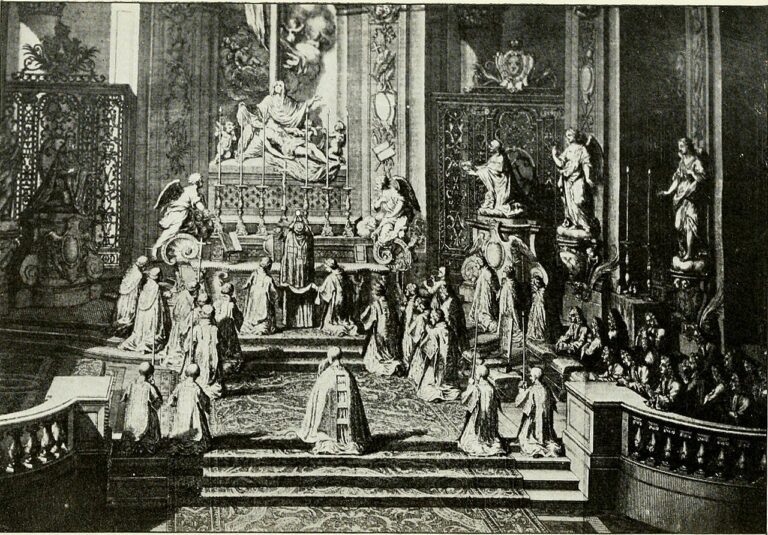

Catholic Mass

The central liturgical right of the Church—the Catholic mass—encompasses the liturgy of the word (the Bible) and the liturgy of the Eucharist (Communion). The liturgy of the word is typically, readings of the Old and New Testaments, a short sermon, and a public profession of faith.

A moral obligation to participate in the Eucharist had existed since early Christianity. The original day for holding communal gatherings that celebrated the Eucharist was Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath. However, in time, Christians began to shift their Sabbath to Sunday. In the 2nd century, Christian philosopher Justin Martyr (100-165) wrote in his First Apology, “And on the day called Sunday, all who live in the cities or in the country gather together in one place…” He goes on to describe the ritual of receiving the Eucharist from a clergyman by those who were qualified to receive it. In 321, Constantine the Great issued an Edict that officially established Sunday as the Christian Sabbath.

In the 4th century the Church introduced written rules about attendance at Sunday mass. Today, missing mass on Sunday is a mortal sin unless the parishioner is “excused for a serious reason (illness, the care of infants) or dispensed by their own pastor. Those who deliberately fail in this obligation commit a grave [i.e. mortal] sin” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2181). The threat of committing a mortal sin by missing mass on Sunday is a social control incentive for Catholics to attend mass regularly. According to Church doctrine, if Catholics leave the Church and no longer attend mass, they are destined to go to hell; simply missing one Sunday mass without a confession of this sin is sufficient reason for damnation!

Changing Theology: Origen and Augustine

Around the time that the Roman Catholic Church was established, it had begun a long-running conflict with independent intellectual pursuits. The conflict began with the Church opposing Pelagius, a monk and theologian whose theology emphasized the primacy of human effort in spiritual salvation. He taught that it was unjust to punish one person for the sins of another; therefore, infants are born blameless.

This conflict continued with the Church’s rejection of the theology of Origen. The early 3rd century theologian, Origen, reflected the state of Christian theology before the rise of the official Roman Catholic Church. The late 4th–early 5th century theologian, Augustine, was responsible for dramatic shifts in doctrinal beliefs over subsequent centuries.

Origen of Alexandria (184-253)

In the years following the death of Jesus in the early 30s, there was much speculation among his followers about him, his nature, his role in the world, and the afterlife. The most influential early Christian scholar and theologian was Origen of Alexandria. He was the most prolific writer in early Christianity, authoring approximately 2,000 treatises, and was the founder of the Christian School of Caesarea. Biblical scholar Elaine Pagels refers to him as the “father of the church” in her bestselling New York Times book, Revelations. John Anthony McGuckin in his book The Westminster Handbook to Origen describes Origen as “the greatest genius the early church ever produced,” and the Encyclopaedia Brittanica hailed Origen as “the most prominent of the church fathers with the possible exception of Augustine.”

One of Origen’s main teachings was the preexistence of souls and reincarnation (also called transmigration of souls). According to Origen, when God created the world, souls that had previously existed without bodies incarnated into bodies. He was an avid believer in free will and taught that disembodied souls have the power to make their own choices. He also believed that the condition surrounding a person’s birth actually depended on what their souls did in their pre-existent state or previous life:

The soul has neither beginning nor end. [Souls] come into this world strengthened by the victories or weakened by the defeats of their previous lives. — Attributed to Origin

Origen did not believe in the suffering of sinners for eternity. Rather, he believed in universal salvation, also known as universal restoration. This doctrine holds that all alienated and sinful human souls will ultimately be reconciled to God because of God’s divine love and mercy.

Origen believed that Jesus had forbidden any kind of violence, including warfare. Firmly believing that war was against the teachings of Jesus, Origen was an avid pacifist.

Origen lived and died for his beliefs. In 250, he was imprisoned by the Romans because he was a Christian. The governor of Caesarea gave specific orders that Origen was not to be executed until he had publicly renounced his faith in Jesus. He endured torture for two years in prison but wouldn’t renounce his faith. He was finally released from prison, but soon after, he died at the age of 69 from the injuries he had sustained there.

Augustine of Hippo (354–430)

Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, who was born one hundred years after Origen died, was to become far more influential than Origen. Of all the Church Fathers, it was Augustine whose teachings ultimately had the greatest influence on the Church and its doctrine, though during his lifetime, his theological and philosophical perspectives were often at odds with other prominent Christian theologians.

Augustine created a theological system that helped lay the foundation for much of medieval and modern Christian doctrine. He believed in an afterlife of an eternity in heaven or hell. He was primarily responsible for formulating the doctrine of original sin, a doctrine that was disputed by many of his contemporary theologians. Among his other formulations are his contributions in developing Just War Theory, which provides guidance for determining whether a war is justified and how to fight a just war. (Augustine is featured in the Kingpins of Christianity and Original Sin chapters.)

Certainly, many of Augustine’s and Origen’s core teachings are diametrically opposed. The following table summarizes differences in their beliefs:

|

Belief |

Origen |

Augustine |

The Church |

|

Reincarnation |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Free will |

Yes |

Yes, but only to sin |

Yes |

|

Universal salvation |

Yes |

No (eternity in Heaven only for the worthy) |

No |

|

Mortal sin |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Hell |

No |

Yes (eternity of suffering in Hell for unredeemed mortal sinners) |

Yes |

|

Fighting wars |

No (immoral) |

Yes, if “just” (Augustine founded the “Just War Theory”) |

Yes |

The Suppression of Origen’s Theology

About 150 years after Origen’s death, some Church leaders who were at odds with his teachings tried and failed to condemn him as a heretic. However, as Augustine’s influence grew, Origen’s teachings became increasingly problematic for the Church. Eventually, in the 6th Century, 300 years after Origen’s death, another attempt by bishops succeeded in condemning him as a Christological heretic. Nevertheless, many Catholics still admired him, and he remained a central figure of Christian theology during the first millennium.

Origen was referred to as the greatest genius the early church ever produced and was even called the “Church Father” by some Christian groups. One would rightfully wonder why he could ever have been declared a heretic by his Church. I believe the correct interpretation was proposed by Charles Stang, Professor of Early Christian Thought and Director of the Center for the Study of World Religions, Harvard Divinity School. Stang’s interpretation appears in the following excerpt of a 2019 lecture, Flesh and Fire: Reincarnation and Universal Salvation in the Early Church:

The emperor Justinian essentially condoned the condemnation of Origen as a means of appeasing a faction that did not appreciate his daring interpretation of the resurrection of the body, nor his insistence on universal salvation. Among other things, bishops worried that preaching universal salvation would undermine people’s piety: if they weren’t motivated by fear of judgment and eternal torment, so the reasoning went, they would grow slack in their faith [italics added for emphasis].

In other words, the members of the Church would no longer fear going to hell, no longer need to believe Church dogma, and no longer need the services of the Church.

According to Helen Ellerbe in her book The Dark Side of Christian History:

The tenets formulated in response to early heretics lent doctrinal validation to the Church’s control of the individual and society. By opposing Pelagius, the Church adopted Augustine’s idea that people are inherently evil, incapable of choice, and thus in need of strong authority. Human sexuality is seen as evidence of their sinful nature. By castigating Origen’s theories of reincarnation, the Church upheld its belief that a person has but one life in which to obey the Church or risk eternal damnation.

Church Excesses

Roberto J. Herrera in his book Reclaiming the Afterlife: Rescuing Our Souls From the Ashes of Religion and the Sacrificial Altar of Scientific Materialism speaks to the wealth accumulated by the Church after the fall of the Roman Empire:

During this period of unrivaled dominance, the Church attained great wealth. It held an astonishing one-quarter to one-third of the land in Western Europe, and these properties were exempt from taxation and without any military obligation to kings. Church income sources included collection of revenue from rulers, confiscation of properties as a result of court judgments, selling the remission of sins (indulgences), selling ecclesiastical offices (simony), and sometimes taking land by force.

At the beginning of the 14th century, Church influence had been declining. In an attempt to strengthen its control over the population and assert its authority, Pope Boniface VIII declared in 1302 that the Pope was only accountable to God, and that anyone hoping for salvation was accountable to papal authority, “… Furthermore, we declare, we proclaim, we define that it is absolutely necessary for salvation that every human creature be subject to the Roman Pontiff” (Boniface VIII, Unam Sanctum, 1302).

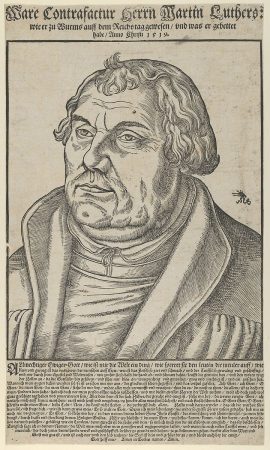

The beginning of the 16th century showed significant discontent with the Roman church. Reactions to the errors, abuses, and discrepancies of the Catholic Church led to the Protestant Reformation, which ended the ecclesiastical unity of medieval Christianity.

The Reformation is generally said to have begun in 1517, when Martin Luther (1483–1546), a German monk and university professor, produced his ninety-five theses. These theses disputed the authority of the Church, particularly papal authority, by denying that the pope is able to remit guilt (by granting indulgences). Among other things, the theses also asserted that the Bible is the central religious authority and that humans may reach salvation by their faith alone, though they should give evidence of their faith with good works. For more information about Martin Luther, see the Kingpins of Christianity chapter.

Luther limited the sacraments to two—Baptism and Eucharist (Communion), for he found no scriptural basis for the others. However, confession and absolution were retained by integrating them into the communion ritual. Belief in sin, salvation, and hell persisted, but the doctrine of purgatory was rejected. Also, John Calvin (1509—1564), a Protestant theologian, pastor and reformer, rejected the distinction between mortal and venial sin, and Protestantism has largely concurred with Calvin.

Early on, Protestantism split into distinct denominations, among them, Lutheranism, Calvinism, and Anabaptism. A major point of contention was whether infants should be baptized. Lutheranism and Calvinism supported infant baptism. In contrast, Anabaptists rejected infant baptism, instead, encouraging children to learn their religion before, hopefully, choosing to be baptized as young adults (baptism by faith).

The early denominations of the Reformation soon spun off new denominations, resulting eventually in many of the myriad denominations that exist today.

Note: Today, many Evangelical Christians still believe that the Bible is the literal word of God. This is despite the multitude of English Biblical translations. The American Bible Society in 2009 estimated that there were about 900 printed versions of English translation Bibles. Which of these, if any, contains the inerrant word of God? How can Christians in good conscience believe the Bible is inerrant, that it is the word of God?

East-West Schism

For centuries, tension increased between the Eastern and Roman branches of the early Church. The tensions finally caused the East-West Schism (Great Schism) of 1054. This schism established the permanent separation between the Roman Catholic Church in the West and the Eastern Orthodox, Greek Orthodox, and Russian Orthodox Churches in the East.In this chapter, however, I will focus on Western Christianity.

Separation of the Anglican Church from Rome

The Anglican Church (Church of England) is distinct in that its separation from Catholicism was essentially a political rather than theological shift. Over the centuries, the Anglican Church had gradually become a distinct branch of the Roman Catholic Church. The English were uneasy with papal authority. Eventually, in 1534, the Anglican Church was separated from papal authority by King Henry VIII to become the state church of England with the king at its head.

However, Anglican doctrine was impacted by the Protestant Reformation. In 1571, the Anglican Church created a list of “Thirty-nine articles” that defined Anglican doctrine as it related to Protestant doctrine and Roman Catholic practice. Faith alone bestows on believers the assurance that the final verdict will be in their favor, but good works are also significant. Like Luther, the Thirty-nine articles recognized only two sacraments—Baptism and the Eucharist—as having been ordained by Christ (“sacraments of the Gospel”) and being essential for salvation. Confession and absolution typically became integrated into communion or prayers. Infant baptism was retained.

In time, other denominations arose from the Anglican Church, among them, Congregationalist, Methodist, and Episcopalian.

Business Model for Church Growth

A business model is a design for the successful operation of a business. Business models must consider revenue sources for products and/or services, the customer base, start-up costs, and expenses. There is an economic realty to every church. The Church’s revenue sources have included donations, tithes, events, capital campaigns and real estate. The customer base is comprised of Catholic believers and potential converts. The services are rituals and practices that play on inherent tension between the fear of damnation and the hope for salvation.

In becoming a major socio-political force in Europe, the Roman Catholic Church developed its business model based on its justification of its authority and by promulgation of its dogmas of sin and hell and the juxtaposed dogmas of salvation and heaven—the stick and the carrot.

The interplay between fear and hope has been fundamental to the success of the Church’s business model. Elaine Pagels summarizes the dynamic underlying church power, as follows:

Christian leaders have understood the use of fear and hope from the time that Justin ‘the philosopher’ (aka Justin Martyr 100–165) threatened Roman emperors with hellfire and courageously defied the judge who ordered him beheaded by declaring that God would bring him back to life. (Revelations, Elaine Pagels)

Regarding the use of fear to manipulate people, Alan Cohen, best-selling author of 30 books (available in 31 languages) states:

Many religions and cultures are masters of manipulation. They have figured out that if you can make a person afraid or guilty, you can control them. If religions deleted fear-based rules, there would not be much left of the religion. True religion is founded in love. Controlling through threat of a horrid afterlife is very convenient because the afterlife is a mystery to those yet to enter it. It’s easy to project morbid stories onto the blank screen of the unknown. (Soul and Destiny, Alan Cohen)

In truth, no valid evidence exists to support the Church’s stick-and-carrot business model. All of the fundamental pillars of its theology are suspect. I will consider the following in some detail: the claim of authority given by Jesus, the notion of sin, and the threat of hell and eternal damnation.

No Authority

Early Christians were mostly poor and illiterate. They learned Church dogma verbally from members of the clergy. At some point in the Catholic Church’s formative years, Church leaders began claiming that the Church was Jesus’ representative on earth, and that its teachings came directly from God. But the Church has never had any actual authority to support this claim. There is no historical evidence that Peter was ever in Rome. Even if he was in Rome, he wouldn’t have had the authority to allow any person or organization to be the representative of Jesus.

The Church justified its assumption of authority by quoting passages from the gospels of Matthew and John. However, claims of authority based on gospel passages are dubious given that the scholarly evidence strongly suggests the books of the New Testament were written by authors who never heard Jesus speak. Therefore, they lacked any authority to write words that he supposedly said.

Moreover, the Church lacked authority to assemble a canonical New Testament by picking and choosing among the many gospels circulating among Christian communities, proclaiming some to be the “Word of God” and proclaiming the rest to be heretical.

No Sin

Sin is a concept created by early Christian theologians in an era when everyone believed that the earth was flat and was the center of the universe. The populace in early Christian times lacked the education and wealth of information that we have today. They were mostly illiterate and ignorant, and they were easily manipulated by fear and hope.

The ignorance of the populace facilitated the creation by the Church of a fundamental mechanism for growth—the belief in sin. With the notion of sin firmly inculcated in the populace, the Church found a willing audience for its first essential service: the ritual of baptism. The Church claimed that baptism was necessary for the remission of sin, so that a soul could, hopefully, be saved.

In 539, the Church affirmed its support for much of the theology of Augustine of Hippo, including his doctrine of original sin. This doctrine denies the truth that babies come into the world as precious, innocent human beings. By claiming that all newborn babies are tainted by an invisible, undesirable quality—original sin—and need to be rescued, the Church was able to preach that all unbaptized people, including newborn babies, were condemned to eternal damnation. They couldn’t get into the kingdom of God. For more information, see the Original Sin chapter.

By justifying the baptism of infants, the Church leveraged its specious dogma of original sin as a social control mechanism over the parents of newborn infants.

No Eternity in Hell (or Heaven)

A core part of Christian teaching is the survival of the soul after death, resulting in an eternity in heaven or in hell. But Christian denominations typically provide only the briefest description of heaven or hell. Why is this? How is it that they focus on the way their members should act here on earth to prepare for a Christian afterlife, while they fail to provide any meaningful information on that afterlife?

Much of the Science-Based Awakening website contains information and resources on the non-material realm that many refer to as the “afterlife.” This popular term is really a misnomer, since Life is a continuum and has neither a beginning nor an end. Consciousness or the soul continues to exist after the death of the body.

In the past several years I have read hundreds of books (many of which are featured on one of these resource pages: near-death experiences, out-of-body experiences, reincarnation, mediumship, and death and dying). I have found absolutely no evidence of any version of a realm or place that involves suffering for eternity. Rather, my research reveals that there are countless realms of existence beyond the physical reality of time and space, contradicting the Christian notion that departed souls are relegated for eternity to heaven or hell.

There are realms that might be considered heavenly and, much more rarely, realms that are perceived of as “distressing.” However, no soul is stuck in any realm. When ready, souls can and do ascend to higher realms. This includes abandoning distressing realms in favor of love-affirming realms. Reports about higher realms invariably include experiences of profound, indescribable love. There is no evidence whatsoever that any soul is ever damned to any sort of hell.

What mainstream Christianity refers to as the “eternal fires of hell” is a clear contradiction of the divine, eternal nature of the soul. The belief in a soul suffering in the fires of hell fails scrutiny on another level. Reports from people who have experienced the afterlife are unanimous in confirming that regardless of the level of physical suffering a soul experiences in a body, once free of the body the soul feels no physical pain.

Modern research into the afterlife has lent increasing credence to Origen’s belief in reincarnation, and this belief is rapidly gaining traction among American Christians. According to 2021 data released by the Pew Research Center, 30% of Christian adults in the U.S. believe in reincarnation. This is up from 24% in Pew’s 2009 survey. For those who haven’t done their own research on the afterlife, an exploration into reincarnation can offer a fascinating look at reality beyond the physical plane of existence. (For more information see the Reincarnation resource page.)

Furthermore, in contrast to Augustine of Hippo’s belief that free will exists only to sin, Origen’s belief in the free will of the soul is also supported by my research on the afterlife. Souls have unlimited potential to make choices both during and between lives. Every soul is on a journey to ultimately merge with its pure essence, which is universal love, the Source of Creation, which English-speaking Christians refer to as God.

In Conclusion

Despite the essential correctness of Origen’s theology, his belief in reincarnation and universal salvation were rejected. Not only did they not fit into the Church’s business model, but they actually undermined it. However, Origen’s theology is clearly supported by research into life after death.

As Augustine’s influence began to grow during the first millennium, Church dogma drifted farther and farther away from a Christianity of love and universal salvation.

Not all Christian denominations use a business model based on invalid claims of divine authority and false beliefs about the existence of sin and hell. I trust that there are those that eschew the fear-and-hope model but focus instead on inspiring their followers with Jesus’ message of love, forgiveness, and acceptance.